Evolution of the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Diagnostic Criteria towards the Gold Coast Criteria

Article information

Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal, neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons (LMNs). Careful history taking, neurological examination, and electromyography are used to confirm its clinical diagnosis. The El Escorial, revised El Escorial and Awaji criteria have proposed varying degrees of diagnostic probability for ALS. However, such categories may cause uncertainty among patients regarding the certainty of diagnosis. Cases labeled as “possible ALS” also risk exclusion from clinical trials. To clarify and simplify the diagnostic criteria of ALS, the previous diagnostic categories of possible, probable, and definite were abandoned in the newly suggested criteria, Gold Coast criteria. The simplified criteria offer practical utility for precise diagnosis of LMN-predominant ALS and clinical trial recruitment going forward.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by the progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons (LMNs), leading to muscle atrophy and weakness [1]. The mean survival time after symptom onset ranges from 3 to 5 years [2].

ALS was first described in 1869 by the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who observed the simultaneous presence of upper motor neuron (UMN) and LMN signs [3]. This classic ALS phenotype, indicative of corticospinal and anterior horn cell involvement, is present in the majority of cases. However, ALS is now understood to exhibit heterogeneous clinical presentations [4].

At one end of the spectrum lies UMN-predominant ALS, where LMN dysfunction might not manifest until years after the onset of symptoms [5]. At the opposite extreme is LMN-predominant ALS, formerly known as progressive muscular atrophy (PMA), which presents with minimal clinical evidence of UMN dysfunction [6]. Patients with PMA may exhibit UMN degeneration in post-mortem studies or through neuroimaging [5,7]. Spanning the range between these extremes are varying degrees of UMN and LMN impairments affecting multiple body regions.

Up to 50% of patients with ALS also develop cognitive and behavioral changes [8], which may progress to frontotemporal dementia. This clinical heterogeneity makes diagnosis challenging, particularly in the early stages. Over the years, several sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed to standardize the diagnosis process.

Changes in ALS Criteria from Past to Present

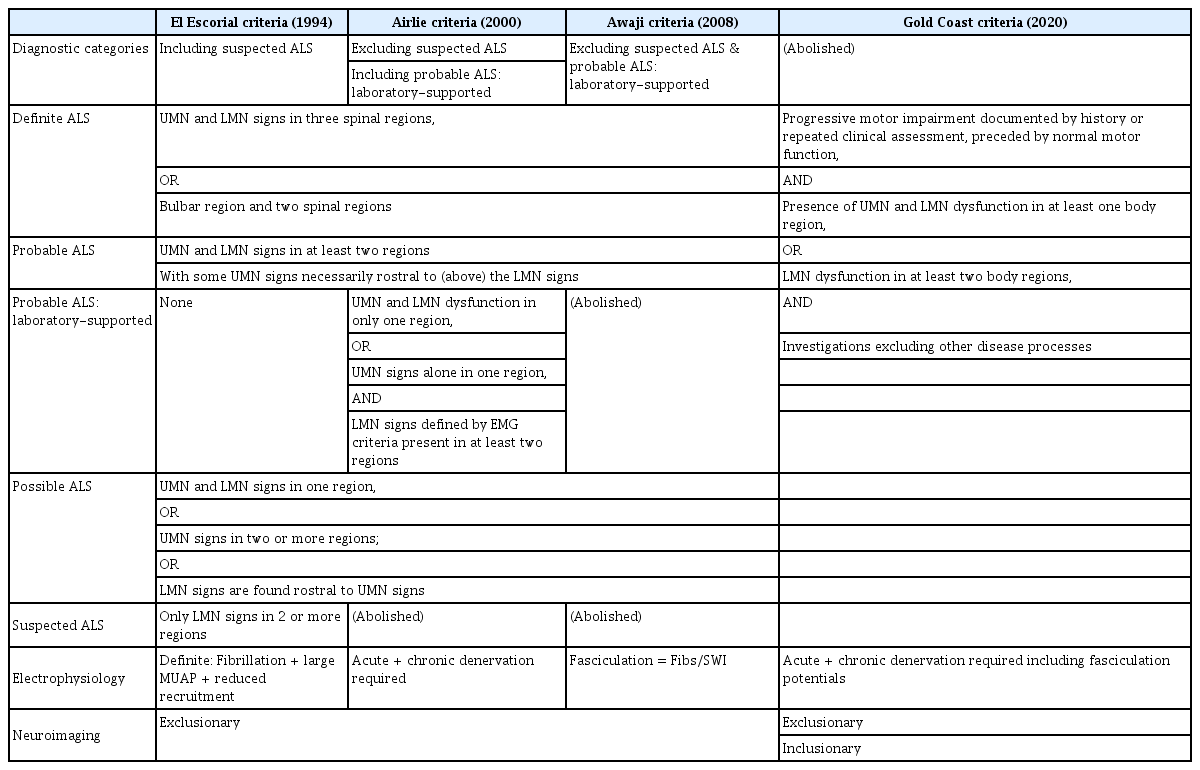

The Lambert criteria, initially proposed in 1957, confirmed the value of electrodiagnosis in evaluating ALS [9]. These criteria include normal sensory nerve conduction studies, relatively preserved motor conduction velocities, and the presence of widespread fibrillation potentials, fasciculation potentials, a reduction in the number of motor unit potentials, and enlargement of motor unit potentials as observed on needle electromyography (EMG) [10].

The Lambert criteria, which depend on extensive denervation for diagnosis, continue to be valuable for confirming cases of advanced ALS [11]. Nevertheless, these criteria have been deemed too stringent, as they are typically only met by patients with advanced stages of the disease [12].

The El Escorial criteria, established in 1990, introduced a category for "clinically suspected ALS," which included not only sporadic ALS but also associated conditions such as ALS plus syndromes, LMN-predominant ALS, and familial ALS [3]. This broadened the range of potential diagnoses, but it also heightened the risk of incorrectly diagnosing conditions such as neuropathies, myopathies, and LMN syndromes as ALS [13].

Another key change in the El Escorial criteria was the acceptance of electrophysiological evidence as proof of LMN signs [14]. This shift was probably influenced by the earlier Lambert criteria and was notable for not requiring clinical manifestations. However, the El Escorial criteria diverged by not recognizing fasciculations, even though they were acknowledged in the Lambert criteria [11].

The revised El Escorial criteria, proposed in 1998, aimed to improve the limited sensitivity of the original criteria [15]. Significant modifications included the elimination of the "clinically suspected ALS" category to reduce the risk of misdiagnosis [13]. In its place, a new category, "clinically probable ALS with laboratory support," was introduced. This category reclassified individuals who met the EMG criteria from "clinically possible ALS" to a status more aligned with probable ALS [16].

The EMG criteria were also simplified; they now accept either active denervation or chronic reinnervation alone as sufficient evidence [17]. Furthermore, the criteria have been expanded to include patient-reported symptoms during history taking as part of the diagnostic process [18]. In light of discoveries confirming genetic underpinnings of ALS, such as the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene [19], a “genetically-determined ALS” category also replaced the former ambiguous “familial ALS” designation.

Through these changes, the revised El Escorial criteria improved specificity regarding ALS-mimicking LMN syndromes but possibly increased false negatives in LMN-predominant presentations [20].

The Awaji criteria, proposed in 2008, further revised the El Escorial criteria [14]. A central aspect of these criteria was the recognition of fasciculation potentials observed on EMG as indicative of LMN involvement, on par with fibrillation potentials or positive sharp waves [21]. This made it possible to interpret all electrophysiological evidence as a demonstration of LMN signs. Consequently, the “clinically probable ALS with laboratory support” category used in the revised criteria was eliminated [22].

By recognizing fasciculation potentials, the Awaji criteria have enhanced diagnostic sensitivity compared to earlier criteria in patients who exhibit fasciculations but lack adequate evidence of LMN involvement [11].

Gold Coast Criteria: New Diagnostic Criteria Complementing Conventional ALS Diagnosis

While numerous criteria have been proposed over the years to standardize the diagnosis of ALS, they have consistently fallen short in terms of sensitivity, reproducibility, and practical utility [23]. The complex diagnostic framework has shown a poor correlation with the actual progression of the disease, leading to confusion among patients about the certainty of their diagnosis [13]. Additionally, there has been considerable variability in interrater agreement when applying the existing criteria [23].

Moreover, criteria demonstrated suboptimal sensitivity in capturing the heterogeneous presentations of ALS, such as bulbar-onset and LMN-dominant forms [24]. Consequently, these cases often do not meet the traditional criteria, leading to exclusion from trials [25]. These persistent issues have prompted a reassessment of the diagnostic process.

In September 2019, an international group of neurologists gathered in Gold Coast, Australia to deconstruct and simplify the diagnostic process for ALS [26]. Prior to defining the Gold Coast criteria, a collective understanding of ALS was established based on several key tenets:

1. ALS is a progressive disorder of the motor system.

(1) It typically has a focal onset, but a generalized onset is also recognized.

(2) UMN signs are not always clinically evident, since they may be obscured by muscle wasting.

(3) Evidence of LMN involvement can be derived from clinical examination and/or EMG.

(4) Evidence of UMN dysfunction is currently mostly derived from clinical examination.

(5) Supportive evidence of UMN or LMN dysfunction can be provided by other modalities such as neuroimaging and biofluids, but they are not necessary for diagnosis.

2. ALS may have associated cognitive, behavioral and/or psychiatric abnormalities, although these are not mandatory for diagnosis.

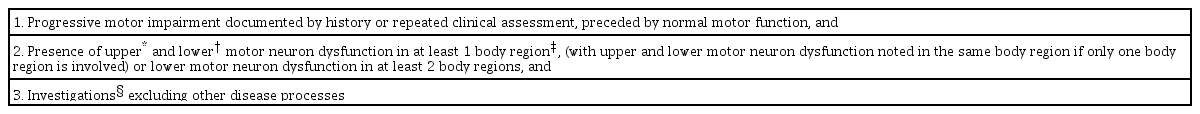

Based on these discussions, new simplified criteria for the diagnosis of ALS, known as the Gold Coast criteria, were proposed (Table 1). The traditional framework categorizing ALS as possible, probable, or definite was discarded. The new criteria were designed to more accurately identify LMN syndromes such as PMA, while excluding certain cases of primary lateral sclerosis that were previously classified as possible ALS.

The key features of the proposed criteria are: (1) the presence of only two diagnostic categories, “ALS” and “not ALS"; (2) the inclusion of motor neuron disease (MND) with pure LMN dysfunction in two or more regions as a form of ALS; and (3) the exclusion of MND with pure UMN signs as a form of ALS.

Recent studies have evaluated the diagnostic performance of the Gold Coast criteria for ALS. Hannaford et al. [22] analyzed data from 506 patients, which included 350 with ALS and 156 with non-ALS neuromuscular disorders. The overall sensitivity of the Gold Coast criteria was 92%, which is comparable to 90.3% for the Awaji criteria and 88.6% for the revised El Escorial criteria when including possible ALS cases. For bulbar-onset ALS, the Gold Coast criteria demonstrated a higher sensitivity of 90.9% compared to previous criteria. Additionally, the specificity of the Gold Coast criteria remained high, although it was slightly lower than that of the Awaji and revised El Escorial criteria. However, this reduced specificity would not negatively affect patient recruitment into clinical trials, due to the mandatory exclusion of mimicking disorders through appropriate investigations.

Similarly, Shen et al. [27] assessed 1,185 Chinese patients with ALS. The Gold Coast criteria demonstrated a greater sensitivity of 96.6%, compared to 85.1% for the revised El Escorial criteria and 85.3% for the Awaji criteria. This increase in sensitivity was most pronounced in patients with limb-onset ALS. However, the specificity of the Gold Coast criteria was lower, at 17.4%, versus over 30% for the conventional criteria. This lower specificity is likely attributable to the study's inclusion of patients who were highly suspected of having ALS, leading to an increased risk of false-positive ALS diagnoses with the Gold Coast criteria due to its less stringent diagnostic requirements.

In summary, the Gold Coast criteria enhance diagnostic sensitivity, though they may exhibit reduced specificity when compared to previous iterations. Nevertheless, with proper investigations, the potential decrease in specificity can be offset by the mandatory exclusion of disorders that mimic the condition in question.

Conclusion

Various diagnostic criteria have been proposed over the past decades to standardize the diagnosis of ALS in research and clinical practice (Table 2). Although revised versions such as the Awaji criteria have addressed the sensitivity limitations of previous criteria, issues related to complexity, reproducibility, and correlation with disease progression have persisted. These challenges have driven the development of a simplified, comprehensive diagnostic framework.

In September 2019, an international consortium of ALS experts convened to distill the key tenets of ALS and to formulate new criteria that reflect recent advances and clinical experience. The resulting Gold Coast criteria exhibit higher sensitivity across various disease stages and phenotypic spectra compared to previous iterations. However, further validation is needed to determine their specificity. Overall, the Gold Coast criteria provide practical utility in capturing the heterogeneity of ALS with fewer categories and a greater focus on clinical fundamentals. This simplified framework may facilitate earlier diagnosis and trial recruitment in the future.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.